Epistemological Possibilities and Their Limits from a Scientific Perspective

My preliminary conclusion may sound like bad news to some:

- We can formulate it paradoxically: the scientific consensus is—and even that is at best a weak consensus—that there is no consensus on the original teaching, or rather, none is possible.

- In the relevant literature, instead of a consensus, we find more of a graveyard or a junk shop of numerous different attempts and hypotheses. All these theories are incompatible with each other. Their proponents always suspect that the proponents of opposing theories, i.e., the opponents of their own theory, merely project their own preconceptions onto the Buddha in a veiled form.

- The crux of the matter here is not a question of content or proof, but of methodology, i.e., the way we investigate the posed question. Now, methodology may be a dry subject for many, one where some prefer to tune out. Nevertheless, I hope to convince you that, on this topic, the problems of methodology actually lead to the answers.

- The entrenched situation is not a result of scientific convenience or confusion. Rather, it is an understandable consequence of the historical relationship between us and the time of the Buddha, which is why there is little hope that the situation will improve anytime soon. I will address the last point first.

Why does science struggle so much to solve this important and fundamental problem?

The Historical Path of Buddhist Transmission

During the time of the historical Buddha, India was still, as far as we know, a purely oral culture. This means that Buddhism originated, developed, and was transmitted over several centuries under the conditions of a certain form of so-called orality (oral tradition).

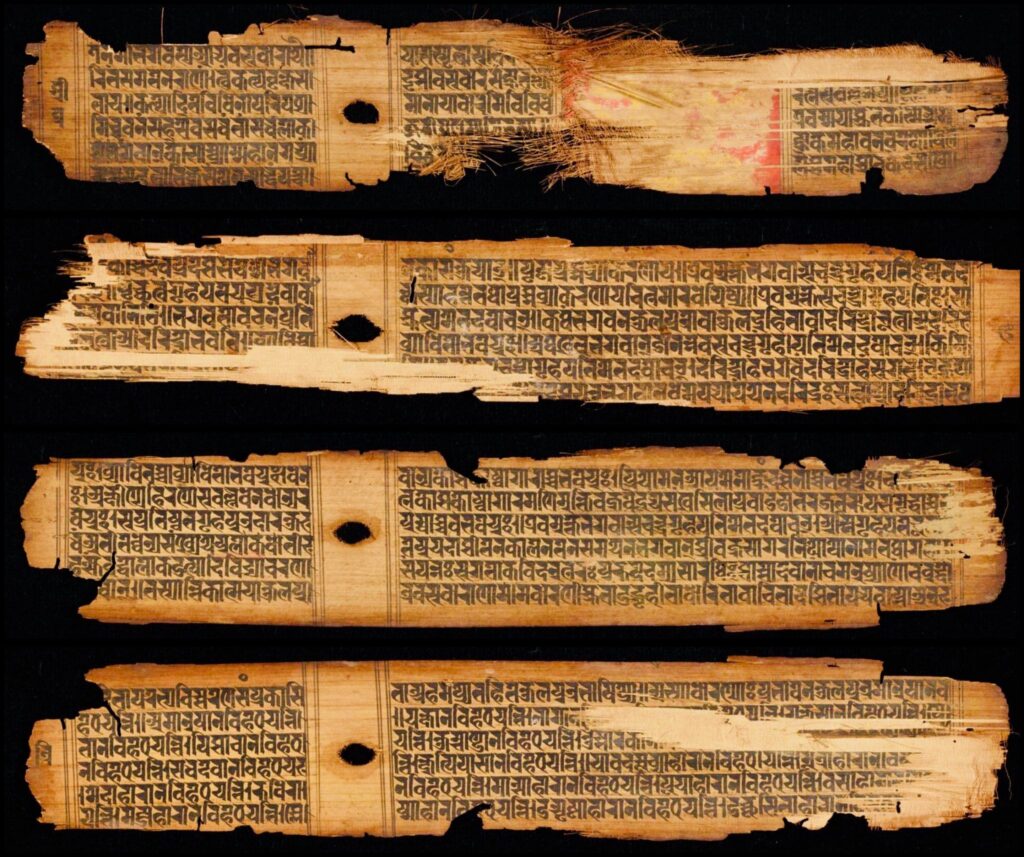

The tradition split into several branches early on—an important point I will return to later—but the earliest known written record of the canon remains that of the Pali Canon, around 100 BCE. The Buddha’s date is also a controversial and possibly insoluble problem, but the majority of experts, following Gombrich, assume that he died around 400 BCE. If that is the case—and this so-called “new chronology” places the Buddha later in history than earlier prevailing theories—this would mean that a completely oral tradition would have existed for at least 300 years before even a single word was written on palm leaves or birch bark.

From Oral Tradition to the First Written Record of the Pali Canon

Now, we must acknowledge the fact that Buddhist traditions have developed very complicated and sophisticated mechanisms to preserve and transmit texts orally with great accuracy, and therefore we must not simplistically assume that oral transmission necessarily leads to a distortion of content. Nevertheless, we do not know by whom or when these mechanisms were invented. To my knowledge, we have no evidence that the Buddha himself could have had anything to do with them, and the mechanisms of oral transmission themselves condition and reproduce a textual design and structuring that cannot be easily separated from the content itself.

Moreover, we sometimes encounter indications that the aforementioned circumstances posed a problem for the tradition itself. This is most clearly seen in Ānanda’s role in the transmission of the Buddha’s words. As traditionally reported, immediately after the Buddha’s passing, a council was convened at Rājagṛha to settle the question of how the teaching should be preserved and transmitted. The most essential core of all versions, according to Tsukamoto’s research findings, is that all the discourses canonized and textually established at this council were first—as it were, the raw material of this process—flawlessly recited by Ānanda.

Ānanda as a Mega-Memory for All Discourses

Ānanda was a cousin of the Buddha who supported him throughout his life as a constant companion to his kinsman and master. From a narrative-logical perspective, this circumstance necessitates that Ānanda and no one else fulfilled this role, because otherwise there would be no one who had heard all the discourses and could therefore have transmitted their content. This means: Every time we hear the immortal words “This I have heard” (“Thus have I heard”, evaṃ mayā śrutaṃ, 如是我聞 etc.), the “I” in it is Ānanda. Theoretically, all the Buddha’s words (buddhavacana) are simultaneously Ānanda’s words.

But immediately following this is the question: That is a considerable amount of texts. How could it be ensured that Ānanda could memorize, learn by heart, and reproduce so much so accurately, word for word? This is especially true considering the fact that Ānanda, when the Buddha was still alive and he was listening to a discourse, could not have known that one day he would have to fulfill the role of an embodied tape recorder? Here, tradition has an interesting solution ready. Among all the Buddha’s followers, it was precisely Ānanda who had the most outstanding memory.

Of course, it is wonderful—literally—when it turns out that the only one who was always present coincidentally had one of the best memories of all time. Now, we cannot, of course, conclude a priori that it is impossible for Ānanda to have possessed such a memory. It can be very well proven that scholars in oral societies in this regard significantly surpassed what is even conceivable for an average modern person. Modern science also reports isolated cases of similar memory feats, such as that of a somewhat pitiable man studied by the Russian psychologist Luria, who is said to have partly formed the basis for Borges’ story titled “The Unrelenting Memory.” Nevertheless, with the prevailing skeptical view of our time, it seems questionable to us whether all of this could truly have succeeded. The thought suggests itself that we are encountering a kind of “just-so story” here, i.e., an etiological legend that covers a sore point like a fig leaf.

Indeed, the facts are more complicated, but I would like to let this sketchy outline stand for the whole. I think the outline of the problem has become clear: Everything we have of the Buddha’s teaching has been transmitted through the bottleneck of oral tradition, which we can vividly imagine as Ānanda’s sole mouth. Thus, it is no wonder that it proves difficult to catch even a faint glimpse of the Buddha himself through this medium.

What Language Did the Buddha Speak?

Due to this type of transmission of tradition, we are inevitably groping in the dark from the outset. An indication of the severity of this problem lies in the fact that we do not even know what language the Buddha spoke, let alone what exact words or sentences he may have uttered in this presumed language.

This fact still seems to remain hidden from some eyes by a widespread myth, namely, the erroneous idea that the Pali language is the original language of Buddhism. In reality, all texts of the Pali Canon are mere translations. Incidentally, it also remained controversial whether Pali was ever a spoken, so-called “natural” language, or if it came into being as an artificial literary language from the outset.

We sometimes encounter another myth on the same topic when we are told that the Buddha spoke and taught in Ardhamāgadhī. Ardhamāgadhī, also referred to as Jaina Prakrit, is the canonical language of the Jaina tradition. For simplicity’s sake, let’s exclude the first compound element ardha-. Māgadhī means “language of Magadha.” Therefore, this assertion seems plausible from a geographical perspective, as the Buddha lived and taught primarily in Magadha, just like the founder of Jainism, his contemporary Mahāvīra. More precisely, however, Jainism faces similar problems to those I am now describing for Buddhism. Ardhamāgadhī is the language in which the earliest Jain texts were written, but this does not justify the assumption that Mahāvīra himself used precisely the same language, let alone the Buddha.

Therefore, cautious and meticulous researchers must approach this question of the Buddha’s own language more indirectly and speculatively. For example, Norman very precisely and extensively examines the Canon against the background of regularities in Pali grammar to uncover deviant forms. On this basis, he argues that occasionally occurring phonemes, endings, or, if we are very lucky, a handful of entire words are relics or traces of the underlying language, and this enables him, as it were, to generalize towards a vague inkling of the characteristics of this language. A good example of the results of his investigations is the fact that “monk” or, more precisely, “mendicant monk, mendicant” is referred to by the word bhikkhu instead of *bhicchu, which would be derived from the rules. Evidently, we are still far from knowing the content of the teaching. Unfortunately, the conclusion must be that, in the strict sense of the word, nothing remains to us of the Buddha’s ipsissima verba —his own words.

Now we have clearly laid out the historical conditions of the problem and its severity. Let us then first ask the question: How do scientists deal with it?—A question that, unfortunately, too often lies too close to a deceptively similar question, namely, how do scientists avoid it?

Philological Methodology – The Linguist’s Toolkit

Here we come to the topic of methodology. In the history of research, several different attempts have been made to solve this problem. The biggest difference is that there are several different preconditions and approaches on which such an attempt can be based. Let us then consider a cross-section of them, so that we can understand the relationships between assumptions and findings.

The Method of “Comparing and Recognizing Patterns”

A first fundamental crossroads that all researchers immediately face is the question of what one thinks of the relationship between conceptual regularities and special cases. The fact is that the Canon, viewed as a whole, contains numerous contradictions and diverging tendencies. At the same time, almost all researchers admit that it contains a considerable degree of repeated, mutually compatible ideas and textual modules, sometimes to an extent that the repetitions become almost deadly boring, unless one is completely intoxicated by piety. Now, the crucial question is as follows: Firstly, where do we locate this unified and massive gravitational center in the overall history and structure of the Canon? And secondly, where do we draw the line between norms and special cases? How many details must deviate from a pattern before we say that the resulting phenomenon is something entirely new and different? Given this sticking point, we are essentially confronted with two opposing ways of thinking.

Either we imagine that the Buddha’s original thought was highly unified and systematic, and the tradition thereafter slowly diverged through misunderstandings, innovations, and mixing; or we imagine that tradition represents or exerts an unstoppable force that gradually unifies, balances, and levels everything. In both cases, we assume a fundamental difference between the founder of the tradition, as a genius standing out from the crowd, and the crowd itself, but in very different ways.

In the first approach, the difference lies in the fact that the founding genius thinks so powerfully and consistently that the masses cannot keep up, whereas the masses are divided and torn and tend towards chaos.

In the second approach, the founder’s genius lies in thinking and speaking so exceptionally. The peculiarity of the masses, on the other hand, would then be that no one thinks for themselves, and in the hands of the masses, everything tends back to the same uniform gray average. Behind these two poles, we can easily recognize patterns that are reflected in typical modern discourses about intellectual giants.

Can Traces of a Pre-Canonical Buddhism Be Recognized?

For example, in the first approach, a small number of earlier studies put forward the interesting thesis that some discourses hidden in the corners of the Canon have transmitted and preserved traces of a so-called “pre-canonical Buddhism.” A good example of this is the teaching of the so-called sixth element. Typically, early Buddhism, like other Indian systems, speaks of four elements, namely, earth, water, fire, and air or wind, or in other words, solidity, liquidity, heat, and motion. Not infrequently, a fifth element is added, namely, space or empty space. However, another variant, according to which there is a sixth element, namely consciousness, is quite rare. Scholars such as Keith, Schayer, and (somewhat later) Lindtner have discussed the possibility that this is a remnant of a very early phase in the development of the teaching. This could potentially represent the starting point of a development. Buddhism could thereby have gradually transformed from a beginning close to the Brahmanism of the Upaniṣads, which represents a monism and in which the mind is central, towards the more radical teaching of anātman—possibly “non-self,” “no-self,” or “egolessness.” I do not mean to say that I find this theory convincing, nor do I want to delve into the theory itself. The point lies rather in the methodology illustrated by this example. The rarity of the teaching of the sixth element within the Canon is understood here as an indication that it was very old and therefore considered authoritative, even though it conflicted with later developed orthodoxy, making it impossible to simply remove it from the Canon. Therefore, according to this theory, it has been preserved like a fossil beneath later layers of the Canon.

But it would also be possible to interpret the same evidence quite contradictorily, starting from the premises of the aforementioned second approach. Let us imagine that an originally pure Buddhism, after becoming popular to a certain degree, attracted converts from the Brahmanical milieu. However, some of them could not abandon the beliefs from their former education at the threshold of Buddhism. Instead, they would have re-clothed a Brahmanical thought pattern in Buddhist terms, with the result that such a hybrid or mixed form would have emerged at the periphery of the Canon.

This example is admittedly a hypothetical interpretation, but similar explanations and hypotheses exist in the literature. For example, researchers have puzzled over why the Canon describes several different models of

Can a Historical Core Be Isolated from the (Pali) Canon?

Let us turn to another type of premise that has also been applied to separate the wheat from the chaff within the Canon and thereby arrive at the earliest teaching. Especially in earlier generations of research, it was often common to assume that a presumed “historical core” lay behind the Canon, which was differentiable from later layers of “accretion,” and even primarily by two criteria.

Firstly, historical events occur in the historical world, in other words, in the material world, where everything always happens in accordance with the laws of natural science and human reason, and not beyond. Thus, there were no miracles, and wherever supernatural events are described, this perspective saw the traces of later additions.

Secondly, the Buddha himself was depicted as a rational human being, thereby justifying a similar approach to the content of the teachings. Where the Buddha’s so-called ‘golden mouth’ speaks of supernatural phenomena, we can also identify inessential later layers and accordingly separate them from the core. At least, that’s the theory. Based on this, some scholars have constructed grand theories about the developmental process of almost the entire canon. However, three major problems arise from this.

Problem 1

Firstly, we have no objective proof that all supernatural components are necessarily later than any other elements. For example, several different versions of the Buddha’s enlightenment story agree that an immeasurable part of the process was the acquisition of knowledge of past lives. Similarly, archaeological evidence for the Stūpa cult is just as early as all textual evidence accessible to us, for instance, in the inscriptions of Emperor Aśoka. Aśoka claims to have enlarged a Stūpa of the Buddha Koṇāgamana from the distant past. However, all knowledge about the Buddhas of the past is based on the same supernatural faculty of our Buddha, which he attained on the night of enlightenment.

A second example: The Sāmaññaphala-sutta/Śrāmaṇyaphala-sūtra, translated by Neumann as ‘The Fruits of Asceticism,’ describes a peculiar phase of spiritual development in a long passage. The meditating monk observes, immediately after mastering the four dhyānas, firstly, that his physical body is dirty, impure, impermanent, and fragile, and therefore unworthy; and that his consciousness is nevertheless, so to speak, a prisoner of this worthless body. Immediately, he creates another body ‘made of mind,’ which he draws from the physical body, like a sword from its sheath, or a snake shedding its skin. With this body, the monk is now able to walk through walls, travel through the cosmos by flying, etc., and he also acquires the ability to hear all sounds of the universe, to directly perceive the minds and destinies of all living beings, etc. Now, this passage, which is rarely mentioned in modern sources, is extremely widespread in the Pali Canon—it appears in 8 out of 13 suttas of the first Vagga of the Dīghanikāya—and the supernatural powers it describes are even more prevalent. This applies almost equally to the Chinese sources. Therefore, this is by no means something inessential, but rather a stable and presumably ancient textual component and idea. In summary, we can say that the supernatural cannot be so easily expelled from the earliest layer of the canon.

Problem 2

The second problem with this theory: Even if we could reliably identify and filter out some later elements, what remains is not necessarily old. We don’t need to go into detail here. It is easy to understand that later tradition-bearers could add inconspicuous, purely doctrinal, even stale elements, as well as fables and miracles.

Problem 3

The third problem is that this methodology is clearly and distinctly based on very simplified notions of intellectual giants and the supposedly common people. Especially intellectual giants, who are supposed to have penetrated the truth, are considered to be as rational as we are, and the reality they perceive is fundamentally identical to, or at least compatible with, what we call reality. The faceless masses, on the other hand, are superstitious, think simply, constantly crave cheap wonder, and tend towards uncritical belief—and this all the more, the further back in the past they are. From these two simplified building blocks, this methodology constructs a simple narrative of an impeccable original teaching system and its gradual corruption by the corrupting influence of the ignorant populace. In some studies, we even explicitly encounter such a tone. I have deliberately chosen the two types of methodology I have mentioned as examples so far because the ways of thinking behind them are somewhat outdated.

Therefore, from our current critical vantage point, it is easier to see all the modern assumptions and biases involved—for example, the idea that the general populace is superstitious and ignorant; or that the so-called world religions are the inventions of timeless, universally valid geniuses who transcend historical conditions and are equally significant for all people of all times, regardless of context. Nevertheless, my aim is not for us to believe that we are now better in the 21st century and no longer fall into such traps so easily. On the contrary, I think we should not so easily look down on our often great predecessors, and I even assume that we are currently making very similar mistakes, the only difference being that we lack the necessary perspective on ourselves to identify these mistakes as such.

The Most Reliable Method for Classifying Historical Buddhist Texts

There are other and somewhat better methods used to identify the early teachings. The most reliable among them is, in my opinion, the comparative method. This method is based on the fact that from approximately the time of Aśoka, i.e., the third century BCE, the community had spread so widely that several somewhat independent transmission groups and branches of the tradition emerged from it. We therefore assume with relative certainty that the narrative material or doctrinal content common to all branches of the tradition is older than this dispersal of the community. Such a methodology has been applied by some of the most outstanding Buddhologists, for example, Erich Frauwallner and Hirakawa Akira, to reconstruct the earliest core of the Vinaya and its developmental history; or Ernst Waldschmidt, to identify the oldest version of the Mahaparinirvāṇa-sūtra—i.e., the Sūtra of Complete Extinction—; or André Bareau, for the same purpose as Waldschmidt, and furthermore, to research the earliest life story of the Buddha as a whole.

This methodology was characteristic of an earlier generation of research around the middle of the last century. Since then, it has somewhat receded. In recent years, however, it has been tirelessly and meticulously applied by Bhikkhu Anālayo and published in several series. This includes, in particular, his groundbreaking and impressive Habilitation thesis, which presents a thorough comparative analysis of the entire Majjhima-nikāya. However, this methodology is very demanding and arduous. To successfully carry it out, one must be proficient in at least Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan, not to mention the modern languages in which the secondary literature is written. Therefore, it is no wonder that we currently do not have nearly as many studies as we would wish for.

The Myth of the Pali Canon as the Original Buddhist Canon

Furthermore, there is probably another reason why this method is not used as often and consistently as would be desirable, namely, the myth of the Pali Canon as the original canon. As already mentioned, the Pali Canon was only committed to writing around 100 BCE. Therefore, the evidence of this single canon alone cannot, strictly speaking, tell us much about the state before the last century BCE. Even when finer methods like linguistic analysis come into play, the possibilities are limited. In comparison, using the comparative method offers more opportunities to access earlier data. In this regard, it seems somewhat astonishing to me how many researchers who are interested in the early teachings and make them the subject of their research cannot read Chinese to this day. This deficiency represents a major weakness in their research.

Even the Comparative Method Is Not the Philosopher’s Stone

Despite its advantages, this methodology also has problems. Firstly, its premises are by no means

A second aspect of the method that gives us pause is the fact that, to a certain extent, it may be more suitable for the analysis of narrative material than of doctrine. Furthermore, there is an even greater problem: Because the dispersal that occurred under Aśoka happened only about one and a half centuries after the Buddha’s passing, this method might lead us to the form of the teaching in the third century, but not beyond that to the teaching of the Buddha himself.

The Principle of Embarrassment and Other Principles

Another group of methods was introduced into our field by Jan Nattier from the area of New Testament studies. These methods consist of a group of three highly interesting presuppositions, namely:

Firstly, something that is embarrassing to the tradition, or puts it in an awkward position, is probably historical and has a basis in facts, the so-called ‘Principle of Embarrassment’.

Secondly, something that is inessential or irrelevant to the tradition is also probably historical, the ‘Principle of Irrelevance’. The idea behind these two principles is that if an embarrassing or inessential detail were not factual, no one in the tradition would have the motivation to invent or transmit it.

Thirdly, something that is forbidden, prohibited, or controversial within the tradition is also probably historical, the ‘Principle of Prohibition’. The guiding idea here is that it would not be necessary to prohibit or criticize something if no one were doing or thinking it.

As an example of the Principle of Embarrassment, we can cite the fact that, according to all branches of the tradition, the Buddha’s biological mother suddenly died seven days after the birth of her son. Even considered a priori, this event does not cast the Buddha in a good light. It is plausible that in pre-modern times, birth complications could be the cause if a mother dies immediately after giving birth to her child. But from the perspective of some branches of the tradition, the Buddha was supposed to be a perfect being; moreover, his last birth was meant to alleviate or end the suffering of all living beings, rather than cause renewed suffering. An indication that the tradition also found this event inappropriate is the multitude of divergent pleas found in later texts. It was already predetermined that the mother would die in her time, so the birth had nothing to do with it; or the joy of being the mother of such a magnificent son was unbearable, and she died of joy; or similar explanations.

In the same way, the fact that the sūtras mention slaves is exemplary of the Principle of Irrelevance. The discourses in which this information appears do not need it at all for the doctrinal content to be clear or meaningful. It only appears as a coincidental part of the backdrop.

For the Principle of Prohibition, we can cite the prohibition of sexual intercourse in the monastic rule as an example. If no monk had sex, such a prohibition would be superfluous.

Based on these principles, we would therefore assume that the Buddha’s mother indeed died seven days after his birth; that slavery was a social reality at the time of the canon; and that some monks engaged in sexual intercourse. However, even this methodology is not sufficient to bring us to the teachings of the historical Buddha. Firstly, these are merely rules of thumb that allow us to uncover historical circumstances. This does not mean, however, that we can thereby determine the date of these circumstances, apart from the obvious fact that they must have occurred by the time the texts emerged. Moreover, these rules tend to bring to light precisely those things that are least connected to the doctrine. The doctrine, especially the core doctrine, is usually not ’embarrassing’ to the tradition; nor is it inessential; and only a small fraction of it consists of prohibitions. Even this method cannot offer us significant progress.

Summary

It can be stated that an overview of the question of what the Buddha himself taught reveals a chaotic jumble of competing opinions and methods. As outlined at the outset, this is to be expected given the structure of historical development and the available sources. I am of the opinion that while we may be able to vaguely deduce some details of the earlier teachings, ‘early’ here does not yet mean as early as Śākyamuni. His own teaching is almost for us

Conclusions – The Dilemma of Modernity

Sociologist Anthony Giddens argues that a fundamental characteristic of modern society is a confluence of risk, ignorance, and expertise. The fact is that we collectively accumulate more and more knowledge. Paradoxically, the abundance of knowledge means that we never manage to master all available knowledge ourselves. As a result, on the one hand, we are aware that we do not know enough to adequately analyze very personal questions, e.g., concerning health, finances, or insurance, on our own. On the other hand, we are therefore constantly dependent on experts.

Ethically speaking, however, it would be immoral for these experts to decide for someone else on matters of ultimate values concerning life and death, because we all firmly believe that every human being is an autonomous entity who should decide such things for themselves. This situation puts us as individuals in a dilemma.

In existential questions, such as in the case of a tumor illness, we rely on the advice of experts, but ultimately one must decide for oneself, e.g., whether or not to undergo a recommended treatment. This means that, even with the involvement of multiple experts, we systematically never know enough to be able to confidently judge which expert to trust and what we should therefore do. This is, so to speak, an unavoidable structural aporia (impossibility of making the right decision in a given situation ) of modernity.

I think the same applies to some things that are historically conditioned, especially when questions of ultimate values are similarly linked to historical conditions. The historical sciences, including philology, are nowadays known to be highly and technically developed, and just as in matters of natural sciences, an educated layperson would not easily dare to draw reliable conclusions about them. However, matters of so-called religion or faith are just as essential for some people as, for example, medical matters, even more so. If we do not clearly acknowledge this dynamic, the consequences could, in my opinion, even be dangerous. In the closely related political sphere, for example, precisely this lack of epistemological (theory of knowledge) certainty prepares the ground on which false prophets like Trump, Erdogan, Modi, or the AfD thrive. Of course, I cannot offer a solution to this profound dilemma.

In the End, It Is a Question of Faith

This dilemma thus also arises when the terms faith or non-faith are applied in connection with Buddhism, as, for example, in the book title Buddhismus für Ungläubige (Buddhism without Beliefs). Strictly speaking, given the previously outlined difficulties of philological research into the earlier teachings, it seems impossible to build or practice a Buddhism without belief, as long as

- Buddhism refers to something that goes back to the historical Buddha or his teachings, and

- by ‘faith’ we understand not only a rigid fundamentalism, but also, in a weaker sense, the usual trust in experts that we all must have, consciously or blindly, in our time, be the relevant experts philologists like myself, or teachers like Stephen Batchelor.

In addition, it must also be considered that all of us, just like the scientists I mentioned today, are forced to make decisions about what counts as a standard of plausibility, and this is ultimately also a matter of faith.

In this respect, the rhetoric of disbelief seems to me to be more of a typical characteristic of modernity; and its application to early Buddhism is the projection of a core belief of a later age.

*Lecture by Prof. Michael Radich, New Zealand Buddhologist at the University of Heidelberg, held at the 3rd Symposium on Secular Buddhism and Community, Heidelberg, 22.11.2019, edited by J. Weber